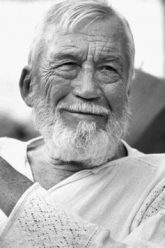

An eccentric rebel of epic proportions, this Hollywood titan reigned supreme as director, screenwriter and character actor in a career that endured over five decades. The ten-time Oscar-nominated legend was born John Marcellus Huston in Nevada, Missouri, on August 5, 1906. His ancestry was English, Scottish, Scots-Irish, distant German and very remote Portuguese. The age-old story goes that the small town of his birth was won by John’s grandfather in a poker game. John’s father was the equally magnanimous character actor Walter Huston, and his mother, Rhea Gore, was a newspaperwoman who traveled around the country looking for stories. The only child of the couple, John began performing on stage with his vaudevillian father at age 3. Upon his parents’ divorce at age 7, the young boy would take turns traveling around the vaudeville circuit with his father and the country with his mother on reporting excursions. A frail and sickly child, he was once placed in a sanitarium due to both an enlarged heart and kidney ailment. Making a miraculous recovery, he quit school at age 14 to become a full-fledged boxer and eventually won the Amateur Lightweight Boxing Championship of California, winning 22 of 25 bouts. His trademark broken nose was the result of that robust activity.

John married his high school sweetheart, Dorothy Harvey, and also took his first professional stage bow with a leading role off-Broadway entitled “The Triumph of the Egg.” He made his Broadway debut that same year with “Ruint” on April 7, 1925, and followed that with another Broadway show “Adam Solitaire” the following November. John soon grew restless with the confines of both his marriage and acting and abandoned both, taking a sojourn to Mexico where he became an officer in the cavalry and expert horseman while writing plays on the sly. Trying to control his wanderlust urges, he subsequently returned to America and attempted newspaper and magazine reporting work in New York by submitting short stories. He was even hired at one point by mogul Samuel Goldwyn Jr. as a screenwriter, but again he grew restless. During this time he also appeared unbilled in a few obligatory films. By 1932 John was on the move again and left for London and Paris where he studied painting and sketching. The promising artist became a homeless beggar during one harrowing point.

Returning again to America in 1933, he played the title role in a production of “Abraham Lincoln,” only a few years after father Walter portrayed the part on film for D.W. Griffith. John made a new resolve to hone in on his obvious writing skills and began collaborating on a few scripts for Warner Brothers. He also married again. Warners was so impressed with his talents that he was signed on as both screenwriter and director for the Dashiell Hammett mystery yarn The Maltese Falcon (1941). The movie classic made a superstar out of Humphrey Bogart and is considered by critics and audiences alike— 65 years after the fact— to be the greatest detective film ever made. In the meantime John wrote/staged a couple of Broadway plays, and in the aftermath of his mammoth screen success directed bad-girl ‘Bette Davis (I)’ and good girl Olivia de Havilland in the film melodrama In This Our Life (1942), and three of his “Falcon” stars (Bogart, Mary Astor and Sydney Greenstreet) in the romantic war picture Across the Pacific (1942). During WWII John served as a Signal Corps lieutenant and went on to helm a number of film documentaries for the U.S. government including the controversial Let There Be Light (1946), which father Walter narrated. The end of WWII also saw the end of his second marriage. He married third wife Evelyn Keyes, of “Gone With the Wind” fame, in 1946 but it too lasted a relatively short time. That same year the impulsive and always unpredictable Huston directed Jean-Paul Sartre’s experimental play “No Exit” on Broadway. The show was a box-office bust (running less than a month) but nevertheless earned the New York Drama Critics Award as “best foreign play.”

Hollywood glory came to him again in association with Bogart and Warner Brothers’. The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948), a classic tale of gold, greed and man’s inhumanity to man set in Mexico, won John Oscars for both director and screenplay and his father nabbed the “Best Supporting Actor” trophy. John can be glimpsed at the beginning of the movie in a cameo playing a tourist, but he wouldn’t act again on film for a decade and a half. With the momentum in his favor, John hung around in Hollywood this time to write and/or direct some of the finest American cinema made including Key Largo (1948) and The African Queen (1951) (both with Bogart), The Asphalt Jungle (1950), The Red Badge of Courage (1951) and Moulin Rouge (1952). Later films, including Moby Dick (1956), The Unforgiven (1960), The Misfits (1961), Freud (1962), The Night of the Iguana (1964) and The Bible: In the Beginning… (1966) were, for the most part, well-regarded but certainly not close to the level of his earlier revered work. He also experimented behind-the-camera with color effects and approached topics that most others would not even broach, including homosexuality and psychoanalysis.

An ardent supporter of human rights, he, along with director William Wyler and others, dared to form the Committee for the First Amendment in 1947, which strove to undermine the House Un-American Activities Committee. Disgusted by the Hollywood blacklisting that was killing the careers of many talented folk, he moved to St. Clerans in Ireland and became a citizen there along with his fourth wife, ballet dancer Enrica (Ricki) Soma. The couple had two children, including daughter Anjelica Huston who went on to have an enviable Hollywood career of her own. Huston and wife Ricki split after a son (director Danny Huston) was born to another actress in 1962. They did not divorce, however, and remained estranged until her sudden death in 1969 in a car accident. John subsequently adopted his late wife’s child from another union. The ever-impulsive Huston would move yet again to Mexico where he married (1972) and divorced (1977) his fifth and final wife, Celeste Shane.

Huston returned to acting auspiciously with a major role in Otto Preminger’s epic film The Cardinal (1963) for which Huston received an Oscar nomination at age 57. From that time forward, he would be glimpsed here and there in a number of colorful, baggy-eyed character roles in both good and bad (some positively abysmal) films that, at the very least, helped finance his passion projects. The former list included outstanding roles in Chinatown (1974) and The Wind and the Lion (1975), while the latter comprised of hammy parts in such awful drek as Candy (1968) and Myra Breckinridge (1970).

Directing daughter Angelica in her inauspicious movie debut, the thoroughly mediocre A Walk with Love and Death (1969), John made up for it 15 years later by directing her to Oscar glory in the mob tale Prizzi’s Honor (1985). In the 1970s Huston resurged as a director of quality films with Fat City (1972), The Man Who Would Be King (1975) and Wise Blood (1979). He ended his career on a high note with Under the Volcano (1984), the afore-mentioned Prizzi’s Honor (1985) and The Dead (1987). His only certifiable misfire during that era was the elephantine musical version of Annie (1982), though it later became somewhat of a cult favorite among children.

Huston lived the macho, outdoors life, unencumbered by convention or restrictions, and is often compared in style or flamboyancy to an Ernest Hemingway or Orson Welles. He was, in fact, the source of inspiration for Clint Eastwood in the helming of the film White Hunter Black Heart (1990) which chronicled the making of “The African Queen.” Illness robbed Huston of a good portion of his twilight years with chronic emphysema the main culprit. As always, however, he continued to work tirelessly while hooked up to an oxygen machine if need be. At the end, the living legend was shooting an acting cameo in the film Mr. North (1988) for his son Danny, making his directorial bow at the time. John became seriously ill with pneumonia and died while on location at the age of 81. This maverick of a man’s man who was once called “the eccentric’s eccentric” by Paul Newman, left an incredibly rich legacy of work to be enjoyed by film lovers for centuries to come.